Circular Economy in Switzerland: A Week Inside the World’s Most Circular Nation

〰️

Circular Economy in Switzerland: A Week Inside the World’s Most Circular Nation 〰️

Anyone working towards more responsible business, operating with purpose, has encountered the ideal of transforming the global marketplace into a circular economy, yet the underbelly of this circular economy many are building towards is elusive and even invisible. Creating a true circular economy that expands borders and designs out waste for good is inexplicably complex, as it requires undoing several decades of linearity that has created its own host of industries that have conquered the market. However, with resource scarcity presenting itself as humanity’s greatest threat (even past climate change according to some experts) there is no pragmatic way forward without a circular economy. Fortunately, circularity is not a completely new concept to commerce, it is simply just re-branded as planetary boundaries are being exceeded at unprecedented rates and a new system to service modern society is becoming more obviously necessary.

In pursuit of a circular economy, the spectrum for progress varies by nation. Some are much further along than others, such as Switzerland, thanks to governmental and civilian support.

As a sustainability delegate, I had the privilege of participating in a week-long expedition to understand how Switzerland is achieving a circular economy across their cities by experiencing on the ground how various entrepreneurs, firms, industries and local governments are putting circularity into practice. From architecture to luxury goods, I learned from changemakers themselves on how they’re challenging traditional, linear business models with uncompromising circular innovation.

Key Learnings:

Circularity is a planning problem. Every potential problem (waste) must be addressed at conception, therefore design thinking is paramount. Planning extends beyond one useful life cycle to conceptualizing how used materials can be indefinitely repurposed and circulated, opting out of the ‘disposal’ option entirely. Scaling circular cycles of a material is essential to the ethos of a true circular economy. The ultimate goal of a circular economy is to eliminate waste, extraction of new resources and circulate every existing material on the planet indefinitely.

True innovation comes as a result from government rather than industry. Government has the power to define the parameters that facilitate groundbreaking innovation from industry by challenging the status quo of business practices that do not necessarily provide value to societal welfare at large (people + planet).

Circularity does not equate to recycling. Recycling should be lower in priority in the circular hierarchy as it does not present as a viable solution to many materials, particularly as the recycling industry scales slowly or even loses traction. Instead pillars such as Refuse, Reduce or Repair should take on higher priority first and blending these pillars together to optimize for material lifetime.

A bottom-up approach that engages every stakeholder will advance a circular economy at the speed planetary boundaries require. This means that from governmental institutions to average citizens, all must favor and prioritize the circular economy at the core of society. Circular thinking must become engrained at a cultural level for a fully functioning circular economy. This cultural transition may be addressed by legislation and policy but also introduced by industry and education to ensure circular consumption is mass adopted and understood by consumers.

A global circular economy is accomplished by hyper-localization and customization. Every country, city, and village is unique and requires its own specific solutions to become fully circular, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on regionality, environmental conditions, available resources and labor, there will be distinct methods to building circular economies around the world, therefore indigenous knowledge will be core to every micro circular economy’s foundation. Additionally, cross-collaboration amongst local entrepreneurs, government, and industry will accelerate the development of local circular economies.

Community-centric design will dominate the circular economy, emphasizing the ‘shared platforms’ model that is central to a circular economy that uses less and maximizes more. Access over ownership will help scale the utilization of any given product or material by way of encouraging sharing rather than individual owning. Cooperatives and shared living are idealistic examples of how a circular economy influences daily life and urges a cultural reset in how civilians live.

Day 1 – Designing Out Waste: Circular Architecture and Hidden Infrastructure in Zürich

Our first day began with an architectural deep dive into Zürich’s circular design ecosystem—an inspiring study in how the built environment can be transformed without demolition.

Freitag Tower: Icon of Industrial Upcycling

Built in 2006 entirely from stacked shipping containers, Freitag’s flagship store embodies the principle of reusing what already exists. The brand—famous for its messenger bags made from old truck tarps—extended that philosophy into its physical space, proving that commercial design can also close loops.

Viadukt: Adaptive Reuse at City Scale

A historical viaduct turned urban marketplace, Viadukt is a masterclass in reuse. Rather than demolish the 19th-century railway arches, Zürich held a competition to reimagine them. The result is a vibrant pedestrian corridor lined with shops, bicycle paths, and art studios—all while trains still operate above. It’s a stunning demonstration of how circularity can coexist with heritage.

Zollhaus: Cooperative Living for a Circular Society

At Zollhaus, land owned by the national rail company was transformed into a 60/40 split of housing and commercial space. The catch? It had to be cooperative by law. Over 100 architecture firms competed, and the winning design created flexible, community-oriented housing with shared amenities—a microcosm of circular living.

Zoo Zürich: Engineering the Invisible Circular Economy

In the afternoon, we explored the rarely seen infrastructure of Zoo Zürich, where circular design meets ecology.

The zoo recycles 70–95% of its water through an advanced filtration system that even captures foliage and animal waste for reuse.

Its geothermal energy network heats and cools enclosures, saving 80,000 CHF annually.

Its restaurant menus are 50% vegetarian, and the zoo replaced its best-selling chicken nuggets with plant-based “Zoo Nuggets,” causing a media uproar but ultimately normalizing plant-forward dining.

As Switzerland’s biggest ice cream retailer, the zoo also persuaded Nestlé to switch to palm-oil-free production, triggering an industry shift.

Behind the scenes, we explored vast underground tunnels, cisterns, and pressurized air systems that quietly sustain this living ecosystem. Even the elephant enclosure’s translucent roof—made of water-pressurized foil cushions—was a feat of circular engineering.

By the first day’s end, Zürich’s taught us sustainability succeeds when design and infrastructure work in harmony, unseen but essential.

Day 2 – Circular Innovation: Academia Meets Industry

Day two at ETH Zürich revealed how Switzerland’s research institutions are shaping global sustainability.

At the sus.lab and Circular Engineering for Architecture (CEA) chair, Dr. Marianne Kuhlmann and Dr. Claudio Martani unpacked the SWIRCULAR project, which uses AI and LiDAR to map the “urban mine”—scanning buildings to identify reusable materials and embedding QR “digital passports” to track their life cycles.

Martani’s team even uses augmented reality to visualize how irregular demolition fragments can be reincorporated into new builds—a perfect blend of behavioral science, data, and design.

Their insight was sobering: only about 1% of Swiss construction currently qualifies as circular. But within a decade, they believe scalable, cost-effective circularity could become mainstream.

Impact Hub Zürich: Where Collaboration Fuels Change

We then toured Impact Hub Zürich, Switzerland’s largest network of purpose-driven startups. Spanning three locations and 800+ members, its model fuses coworking, gastronomy, and corporate events to foster cross-sector collaboration. It’s a living ecosystem of circular entrepreneurship.

Zuriga AG: Repair Culture in Action

Next, we visited ZURIGA AG, a local espresso machine maker. Every device is modular, repairable, and made-to-order—assembled in just 45 minutes and designed for a 20-year lifespan. No glue, no welding, just bolts. Their repair shop and upgrade program prove that durability can scale profitably.

QWSTION: Fashion Without Waste

Finally, we met QWSTION , creators of Bananatex® —a fully biodegradable textile derived from banana fibers grown in permaculture. Their products are plastic-free, designed for disassembly, and even compostable within weeks. Through their Second Cycle subscription, customers can rent or repair bags instead of replacing them.

Together, these innovators demonstrate a truth at the heart of Switzerland’s circular success: collaboration—not competition—drives innovation.

Day 3 – Basel: Where Policy Meets Purpose

The third day took us to Basel, a city turning policy into planetary action.

Netto-Null Basel 2037

Basel has legally committed to net zero by 2037, embedding climate targets into its constitution. According to Nicolai Diamant from the Basel-Stadt canton, the plan relies on expanding district heating, scaling renewables, and developing a carbon capture site near its incineration plant—with waste CO₂ shipped to Norway for storage.

BaselCircular: A Public-Private Engine for Change

The BaselCircular program dedicates 2 million CHF annually for eight years to fund circular economy projects. Its mission: help established companies and startups integrate reuse, resource efficiency, and innovation into their core models.

Francke Areal: Circular Urban Regeneration

We toured Francke Areal, a former industrial site now reborn through circular restoration. The Eckenstein-Geigy Foundation, led by Gabriel Eckenstein, has turned old buildings into community spaces for circular entrepreneurs and cultural projects. Every plot carries both a financial and carbon budget, pushing designers to maximize reuse.

Here, circularity becomes tangible: façades rebuilt from on-site materials, gates fashioned from salvaged metals, and wastewater reused through plant filtration. Even urine is processed into fertilizer—a literal closed loop.

ten23 Health: Circularity in Life Sciences

At ten23 health , a pharmaceutical manufacturer and certified B Corp, we learned how the sector is tackling resource scarcity. Their initiative “Go Circular in Life Science” convenes industry peers to share circular practices—proving that collaboration can outpace competition, even in pharma.

Basel’s greatest lesson: Circular economies depend on infrastructure as much as ideals. Storage, logistics, and skilled labor are as critical as innovation itself.

Day 4 – Building the Future from Waste: The Circular Construction Revolution

Day four took us deep into the mechanics of reuse, starting with Eberhard Unternehmungen in Zürich—Switzerland’s largest recycler of concrete.

EbiRec and EbiMIK: Concrete & Housing Recycling

At EbiRec, over 300,000 tons of concrete are recycled annually through meticulous sorting: sieving, wind sifting, and precision silos that separate aggregates by grade. At EbiMIK, a robotic sorting line identifies up to 25 fractions of materials from demolished homes—turning chaos into clean input for new builds.

Their proprietary product Zirkulit is a fully recyclable concrete alternative that meets performance standards for structural use.

Intep – Integrale Planung: The Systems Thinkers

Later, we met with Intep – Integrale Planung GmbH , whose consultancy unites sustainability, architecture, and policy. Founded in 1979, they were early pioneers of “dematerialization” and “decarbonization.”

Their Zurich headquarters, Kulturpark, demonstrates circular architecture through modularity, affordable housing, and permeable green infrastructure.

Key takeaways:

80% of Swiss waste comes from construction.

Switzerland uses 7.5 million tons of building materials annually; 30% must be circular to meet future goals.

Actual circularity today: below 10%.

Goal: at least 30% reuse for all new builds.

As their cofounder put it, “People believe we can consume whatever we want and put the rest aside. But that’s not the case.”

Circularity here is framed not as sacrifice but as economic advantage—the new metric of quality.

Day 5 – Closing the Loop: From Industrial Heritage to Modular Futures

This day traversed the country—from Zürich to Winterthur, Bern, and Lausanne—showcasing how circularity can adapt to any context.

K118: Form Follows Availability

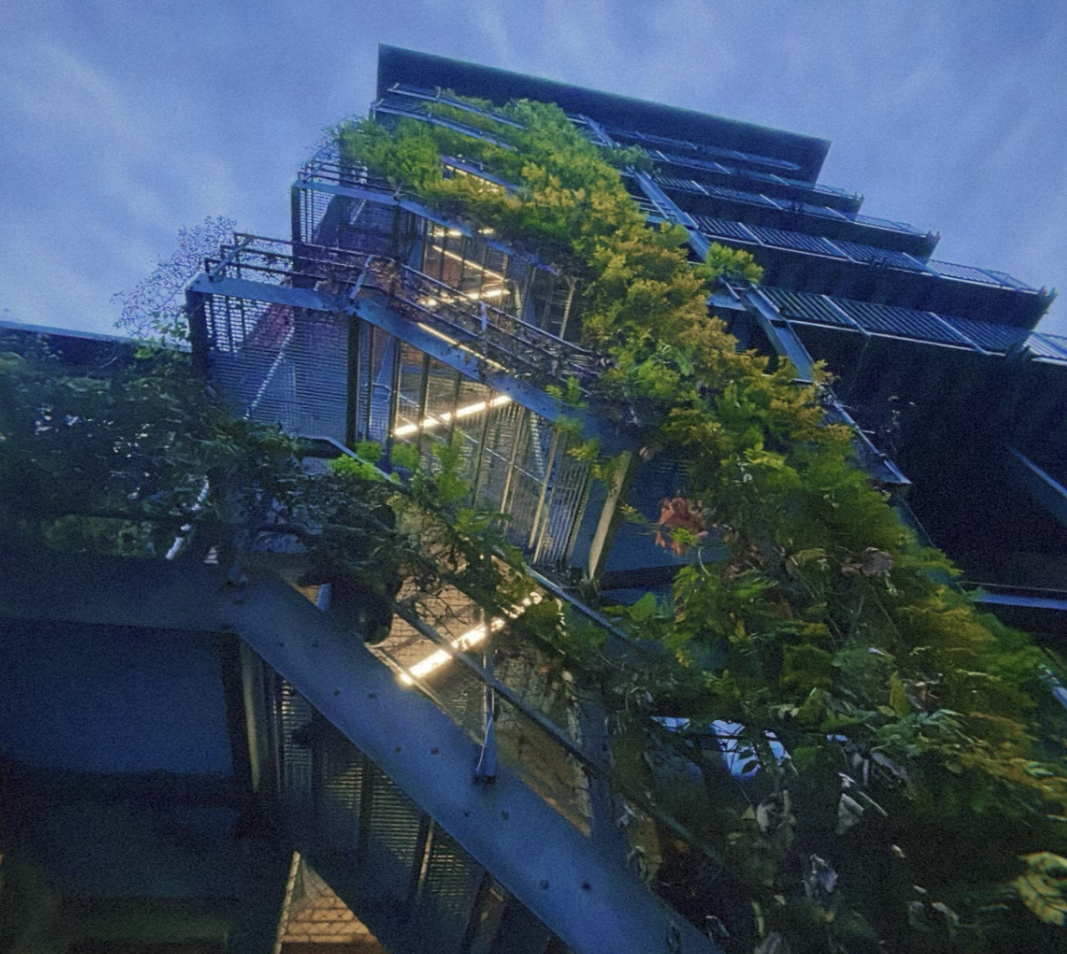

In Winterthur, we toured K118, a pioneering adaptive reuse project by baubüro in situ ag. The building adds three new stories atop a former factory using steel beams and façades reclaimed from nearby demolitions. They also have used solar panels which underneath house biodiversity through recycled concrete and weeds that host living soil.

Designers coined the term “Form follows availability”—embracing the imperfections of used materials. They even created a magenta color code in architectural drawings to indicate reused elements. The result: 58.6% emissions reduction, achieved within cost parity.

NEST: The Living Lab of Circular Construction

Next stop, NEST (Next Evolution in Sustainable Building Technologies) at Empa, where researchers build modular units to test new materials and energy systems. Some projects reach 90% circularity, proving reuse can match the cost of virgin materials.

Here, circularity becomes experimental, not hypothetical—students live in prototypes, feedback loops are real-time, and innovation happens through failure and adaptation.

Bern: Circular Industry at Scale

In Bern, we met Dr. Sebastian Friess and Isabelle Berthold from the Economic Development Agency. Their focus: enabling circularity across Switzerland’s key industries—precision manufacturing, food systems, and micro-technology.

Highlights included:

#tide: transforming ocean plastics into watchbands and tools.

Cemiplast: innovating micro-injection molding for medical and food applications using recycled materials.

A cheese manufacturer reducing emissions by 60% through smaller recycled tools and sustainable packaging.

As one local entrepreneur joked, “We have a lot of winter and we’re very precise—so we’re good at making small, perfect things.”

Day 6 – Nature, Time, and Regeneration

Our final day was both poetic and grounding—a reminder that circularity is not just mechanical but ecological.

Lutry: Biodynamic Viticulture

We began in Lutry, riding through the UNESCO-listed vineyards by train and tasting biodynamic wines where grapes, stems, and compost are cycled back into the soil. Grapes even hung from ceilings as they prepared for special natural fermentations.

Here, circularity tasted tangible—alive, microbial, regenerative.

ID Genève Watches: Redefining Circular Luxury

In Lausanne, we visited ID Genève Watches , the first B Corp–certified Swiss watchmaker, and arguably the most innovative luxury brand in Europe. Their Circular S and Circular C collections are made from solar-melted recycled steel, straps crafted from orange peels and hemp, and nanotech finishes that create color without pigment.

Each watch carries traceable provenance codes engraved into its body. Even the packaging is compostable mycelium and seaweed fiber. Investors like Leonardo DiCaprio have joined, but their message remains human-scale: luxury should be repairable, traceable, and circular.

EPFL Structural Xploration Lab: The Future of Building with Waste

Finally, at EPFL’s Structural Xploration Lab, researcher Maxence Grangeot showed us how to reuse concrete rubble for structural walls—reducing virgin material use by 80%. Through 2D scanning, digital mapping, and pre-fabrication, his team can rebuild multi-story buildings from discarded fragments.

His statement summed up the week: “Reuse requires new expertise.”

Circularity as Culture, Not Just Commerce

By the end of six days, one lesson stood taller than the Alps around us: Switzerland’s circular economy isn’t a policy, it’s a mindset.

From Zurich’s geothermal-powered zoo to Basel’s carbon budgets, from ETH’s AI material passports to Lausanne’s solar watches, every corner of this small nation proves that circularity scales through design, governance, and shared purpose.

Circularity here isn’t just business, it’s culture. It’s how people vote, how they build, and how they live.

If the world is to close the loop, it won’t happen through technology alone. It will happen through trust, creativity, and collective will, the same forces that make Switzerland a living laboratory for the circular future.

Because in the end, a circular economy is not just about what we reuse, it’s about what we choose to value.